Yes, I realize that title is ridiculously long. It is crucial we—the collective cultural “we”—understand the relevance of chattel slavery to where we find ourselves now in America in a cultural sense, because all that we have is built on all that has been, and many Americans from every part of the country, every economic class, and every color have not been taught relevant facts about our history (alternate link).

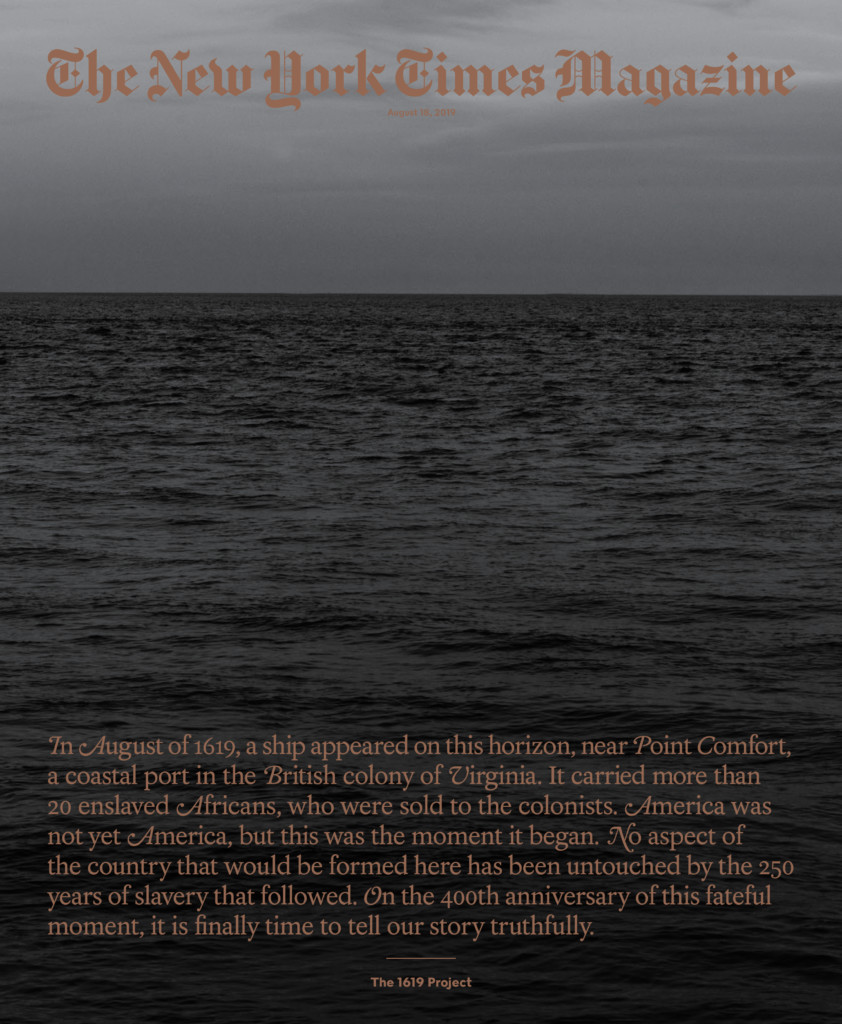

Our history curricula have neglected and whitewashed critical elements of the context in which events happened, people became notorious or famous, and legislation and court decisions have shaped what was allowed by whom and against whom. This project, by The New York Times Magazine in collaboration with the Smithsonian—the lead essay of which, by project director Nikole Hannah-Jones, won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Commentary—aims to help correct that by filling in gaps in knowledge and understanding of adults and providing new free curriculum for students at all levels, co-developed with the Pulitzer Center, which hosts it.

In response to criticism from historians, The Times updated a sentence in Hannah-Jones’ essay to clarify that, while fear that England was headed toward outlawing slavery was a primary factor driving support for the American Revolution among some colonists, it was not for all colonists. In fact, throughout American history there has been conflict between those Whites who supported slavery, racialized castes, and White supremacy and those who have ardently resisted them.

If you’re a subscriber to the Times, you can read the essays in the 1619 Project and explore its interactive elements here. If not, you can download a PDF file of the full issue of The New York Times Magazine issue containing all the essays from the Pulitzer Center.

It’s no wonder blatantly racist Senator Tom Cotton objects to the project, and especially to the curriculum, along with the Clown Prince of Darkness, the National Review, the New York Post, Breitbart, and other media outlets which support White supremacy (in its stealthier form, without the sheets and hoods). A common objection from that side of things is that the contributions were made primarily by Black writers, who they believe biased on the subject, while they think White writers are somehow impartial, a misperception which comes up again and again in American culture, not just on the subject of race and racism but for all the “isms”: sexism, heterocentrism, ableism, and so on, where the privileged majority is seen as impartial while the affected and disempowered are seen as agenda-driven. Educating Americans on the true impact of slavery, particularly on current positions and rhetoric from right-wing politicians and commentators, is against their interest in maintaining support for their policies, campaigns, and arguments. Last Thursday, Cotton introduced legislation to prevent teaching American students the truth about our history, and on Sunday he gave an interview to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

According to The Guardian, Cotton, whose proposed legislation—misleadingly entitled Saving American History Act of 2020—“would prohibit the use of federal funds to teach the 1619 Project by K-12 schools or school districts”, according to a statement from the senator’s office, told his hometown newspaper:

“The entire premise of the New York Times’ factually, historically flawed 1619 Project … is that America is at root, a systemically racist country to the core and irredeemable,” Cotton told the Democrat-Gazette.

“I reject that root and branch. America is a great and noble country founded on the proposition that all mankind is created equal. We have always struggled to live up to that promise, but no country has ever done more to achieve it.”

He added: “We have to study the history of slavery and its role and impact on the development of our country because otherwise we can’t understand our country. As the Founding Fathers said, it was the necessary evil upon which the union was built, but the union was built in a way, as [Abraham] Lincoln said, to put slavery on the course to its ultimate extinction.”

The chief problem with this perspective pushed by Cotton and his allies is that the United States is, in fact, a systematically racist country at its core, but the advocates of teaching that through history and context do so because we believe that it is redeemable. If we believed the country was irredeemable, as Cotton said, there would be little point to putting energy toward making history education more accurate and teaching the public about the broad and deep impacts of racism on the country. The struggle to which Cotton refers, to live up to the promise that we are all created equal, has been driven at all times by Black Americans and their allies among other racialized groups, not by the comfortable White majority, and opposed at all times by the conservatives of that moment. Hannah-Jones responded to Cotton and challenged him to either align himself with or repudiate the characterization of slavery as “necessary evil”.

“He loves his country best who strives to make it best.” — Robert G. Ingersoll

I challenge you, dear reader, to consume as much of the contents of the project as are available to you, to sit with any discomfort and insights you may have regarding the information and implications and reflect on them, to look into any questions you may be left with, and to share the information and any changes to your perspective with your family and friends, especially your children or grandchildren if you have them.