American conservatives this week are up in arms about a graphic shared by the National Museum of African American History and Culture which addresses some of the ways in which white culture is dominant and has become the default cultural setting in the US. They made such an uproar about it that the museum removed the graphic, rather than engaging in conversation about it and perhaps learning something. White culture is so much the American default that we often don’t see it, just as fish don’t see water until they’re taken from it.

“The whole idea behind the portal is how do we give tools to people to have these conversations that are vital to moving forward. This was one of those tools,” interim director of the museum Crew told the Washington Post (alternative link without paywall). “We have found it’s not working in the way we intended. We erred in including it.”

But Crew said the chart is not racist. “We’re trying to talk about ideology, not about people,” he said. “We are encouraging people to think about the world they live in and how they navigate it. It’s important to talk about it to grow and get better.”

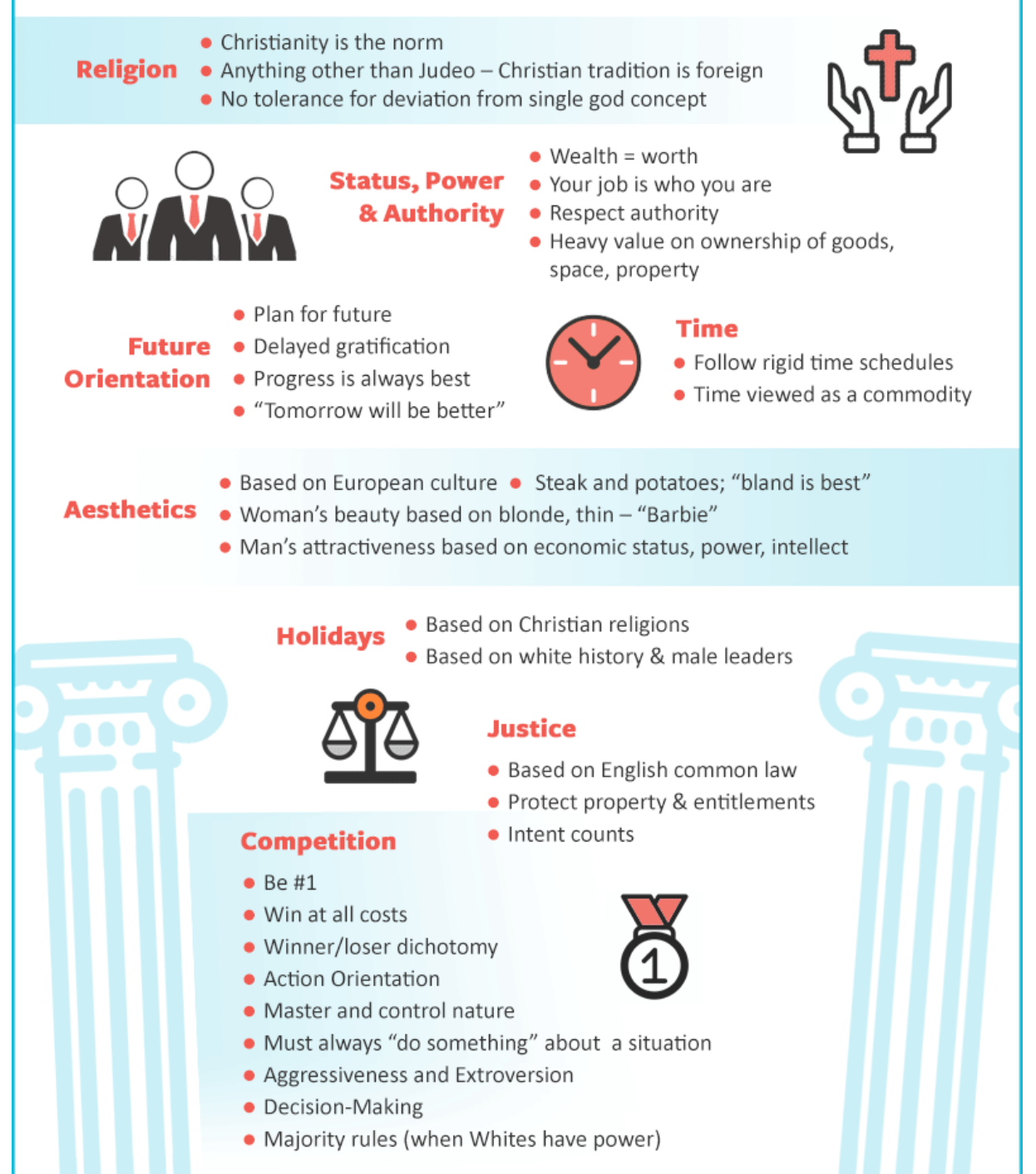

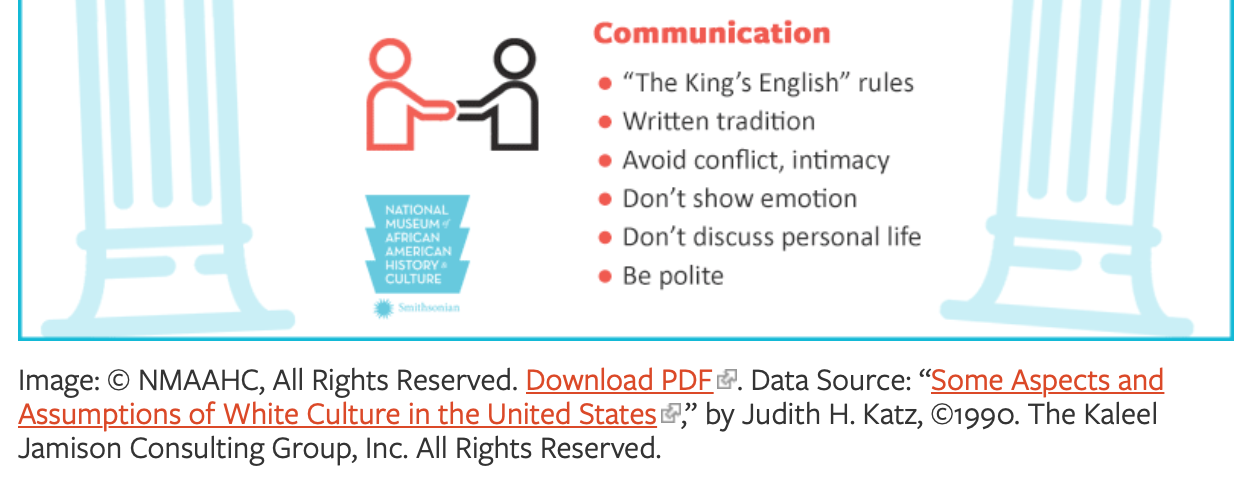

Here is the graphic in question (in pieces, as found):

Ben Shapiro and Donald Trump, Jr., both of whom tweeted outrage against this, and other fragile white people or other people who are deeply invested in the American status quo may find this threatening (sadly for them, it seems their world is a very scary place—I’m thankful mine is not), but that doesn’t make it untrue or inaccurate. It shouldn’t even be controversial to say that the dominant culture in the US is heavily based on Western European culture, ancient Southern European/Mediterranean culture (Greeks and Romans in particular), and Judeo-Christian culture. Republicans love to refer to “Judeo-Christian values”, but apparently object to having it pointed out that the Judeo-Christian values which are culturally dominant are those from white Jews and Christians of European heritage.

I’m not going to try to address every point in the graphic. That would be worthy of a book, and to treat the subject properly would take a lot more broad and specific cultural knowledge than I have. I will, instead, tell you some of what I do know about some of the points within it, and urge that you seek out more information, both by talking with people whose culture or subculture is different from yours and by reading and consuming other media about less familiar cultures, both contemporary and historical, as I will continue to do. Like the fish that doesn’t see the water it’s in until it’s out of it, it’s hard for us to see what defines our culture until we find some of its edges or leave it entirely. It’s critical that we recognize and accept that there is no inherent superiority to our culture just because it’s ours and familiar.

- First, the American value uplifting “rugged individualism” is completely foreign to many cultures, including ones originating in the US (Native cultures, of which there are hundreds with many differences among them), Central and South America, Africa, and Asia. In many cultures, family, tribe, or community is foremost, and the group is seen as succeeding or failing together, traits and actions of the group members reflecting on the whole. While some may see this as erasure of the individual, others see it as placing the individual firmly in a context and moving some of the pressure toward perfection away from the individual and toward the group, if any exists.

- Nuclear family structure is a bit like individualism extended to the family. It usually consists of one or two parents (or a parent and partner) and one or more children, with the occasional addition of an “extra” family member because of a special situation, often having to do with insufficient funds for separate households or the “extra” person being in need of special care of some kind.

This structure is also common in Western Europe, but in most of the world, it’s less common than extended family households, where multiple generations live and work together, sharing responsibilities for providing for the household, caring for children and other family members in need, and doing the labor to upkeep the household such as chores. In the United States, adoptions can be denied—even of family members—or children removed from the home for failure to follow the dominant culture’s way of doing things, including giving children their own rooms, even if that’s uncommon in the culture of the family involved.

- It’s no secret that American education heavily emphasizes teaching Western European history and literature, a way of transmitting culture to the next generation. We’ve had to establish February as Black History Month just to get black Americans mentioned to students beyond the few token figures typically included in the curriculum. Our students are taught much more about European history than the histories of the rest of the world, despite some cultures (most notably China, with its extensive written records) having considerable authoritative sources and all the rest having rich oral traditions and various anthropological and archaeological evidence from which to teach their histories, and in spite of the considerable contributions many of them have made to world knowledge.

- The Protestant work ethic presupposes equal opportunity for all in assigning blame to those who do not succeed by American standards, despite mountains of evidence that we’ve never yet provided a single generation with equal opportunity. Exceptional people are held up as the standard by which all from a community should be judged, when that community is primarily made up of BIPOC or low-income people, rather than using the baseline experience as evidence that more should be done to help others succeed by the same standard. Likewise, the dominant culture tends to reject alternative constructs of success, which is as cruel as it is ridiculous. How long would we survive as a nation if every one of us were a doctor, lawyer, politician, or corporate executive? Not long at all. We need our caretakers, hospitality workers, maintenance workers, artists and musicians, writers, thinkers, teachers much more than we need the people in charge of them.

- Likewise, as part of how we construct success, we expect part of that to be aiming to own a home of some kind, possibly some land, often a vehicle (typically a “status” make), and various consumer goods. Our law is largely about the rights of property owners, and our law enforcement can be much more zealous in defending those rights than the rights of individuals or groups (see, for example, the large deployment of law enforcement resources against the Water Defenders resisting pollution of water used for drinking, bathing, and other household needs at Standing Rock, despite all the property involved being owned either by a private corporate entity or sovereign tribal nation).

Many cultures do not and have not placed such emphasis on ownership, especially individual ownership, and whatever is owned may be owned by families, tribes, or communities. When European immigrant colonizers were paying various tribes for land rights in the early days of this country, it was not uncommon for the deal to be seen as ridiculous by the Native participants and onlookers, because no one could own land; it owned itself, as anyone could see.

- Communication comes in many forms, most of them nonverbal. We communicate through posture, eye contact, costuming, hair styling, gestures, things left unsaid, approach, and how we carry ourselves and hold ourselves. How we introduce ourselves is a very culturally informed form of communication: if you were from many Native American tribes, you would give your tribe/tribes, clans, and family or parents before giving your name, while white culture says give your individual name first, family name second, and relevant group affiliations last (“Hi, I’m Bob Smith from Accounting”).

White culture also emphasizes “respectability”, as understood through a Western European lens. You are supposed to “look respectable” by white standards to engage in any activities outside of your family and immediate social group, such as attending school, competing in sports, getting hired and working, interacting with the justice system or other government agencies and functions, and that very much includes dressing according to white standards of respectability and styling your hair by the same standards, which has burdened and excluded Black people especially consistently by finding dreadlocks, braids, twists, poofs, and other natural hair styles unacceptable. Applicants assumed to be Black based on their names get half as many callbacks on their identical resumes as those assumed to be white, and I’m sad to say that represents significant improvement.

Even when resisting, protesting, or educating about the many forms of white supremacy, white Americans (and sometimes others who have internalized white cultural expectations) often try to impose expectations of respectability according to white standards: don’t be the “angry Black” person or you won’t get heard, don’t mention white people or whiteness or white privilege or white supremacy if you don’t want to alienate those who aren’t already on your side, don’t inconvenience white people or make them uncomfortable or you’ll lose them before you start because their comfort and convenience are more important than your safety, ability to support yourself or your family, or even your freedom.

People like Ben Shapiro and Donald Trump, Jr., who got so outraged by this graphic operate from a place where the status quo can’t be challenged and everything and everyone that operates outside of their comfortable paradigm is threatening. Don’t be like that. Be inquisitive about what is outside your knowledge and experience. Fall into some internet rabbit holes learning about different cultures, history you’re not already familiar with, ideas you find provocative, perspectives different from your own. When you find people talking about things that make you uncomfortable, unless they involve hurting the vulnerable, sit and listen and reflect on what you hear, without inserting yourself needlessly and certainly without centering yourself, your ignorance, or your discomfort. When you find people willing to educate you, be gracious about the gift they are giving you, even (especially) when it makes you uncomfortable. How much bigger and richer our worlds become when we let difference in!